Registration Open!

Join the NYG&B and other genealogy experts for New York’s largest statewide family history conference:

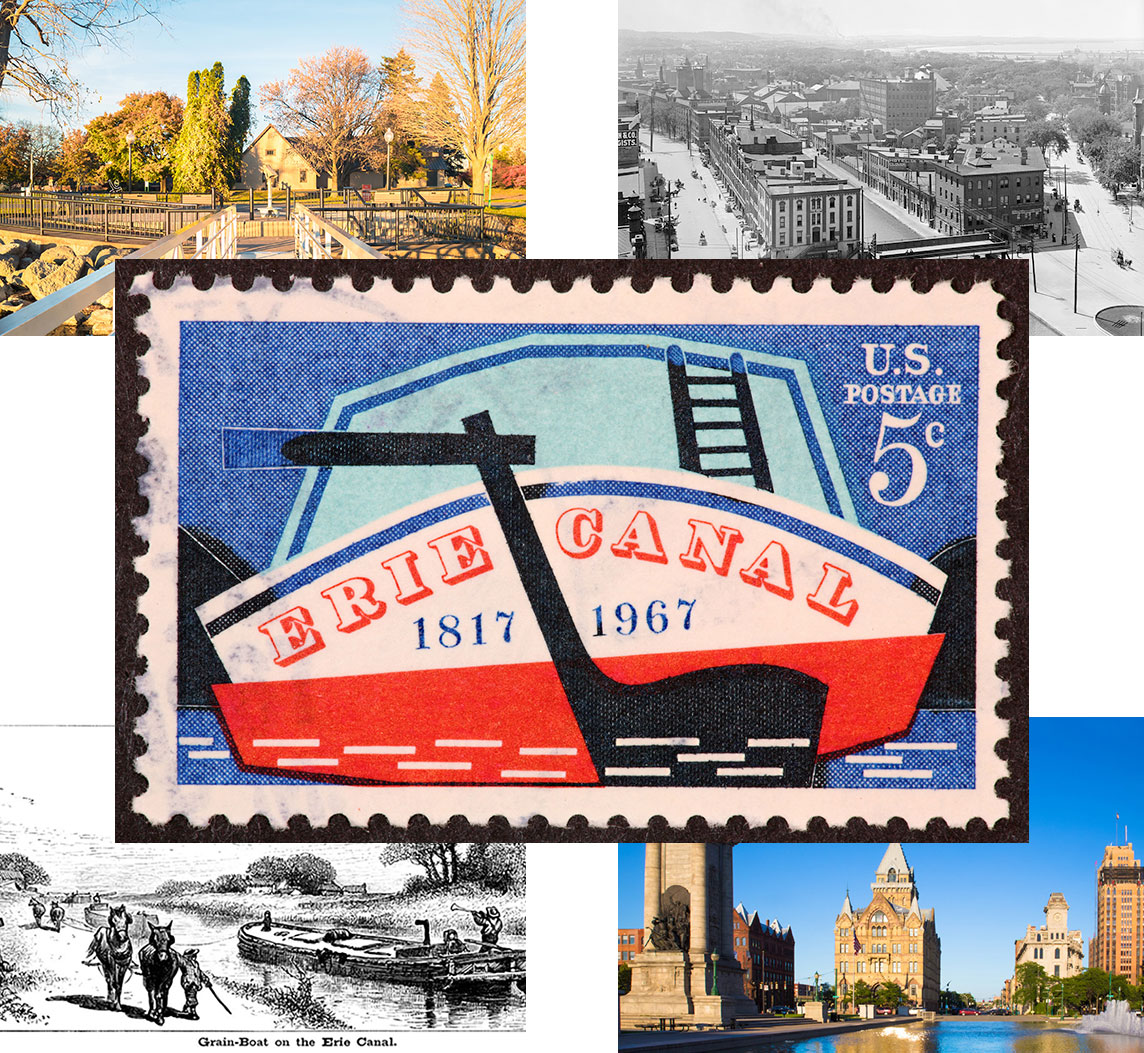

- September 20–21, 2024 (Livestreamed from Syracuse, NY)

- September 20–November 1, 2024 (On-Demand Access)

This year's theme is Connect at the Crossroads and will feature livestreamed presentations in Syracuse, New York, as well as on-demand sessions to watch at your own pace. Can’t join us in person? No problem! All in-person events will be livestreamed and subsequently made available on demand.

From the essentials needed for navigating New York research to using maps, newspapers, letters, and journals on your historical journey to understanding immigration and migration patterns, the conference offers a rich array of sessions to help participants hone their skills.

The livestreamed portion of the conference will be held on Friday, September 20 and Saturday, September 21, 2024, at the Erie Canal Museum in downtown Syracuse (318 Erie Boulevard East, Syracuse, NY 13202). All the conference programming and sessions will be available to registrants for on-demand viewing through November 1, 2024.

What to Expect

- More than 20 of the top voices and experts in the genealogy field to lead sessions and answer your questions, including Michelle Tucker Chubenko, Skip Duett, Annette Burke Lyttle, Jeanette Sheliga, Jane E. Wilcox, and more.

- A total of 34 sessions and events (13 in person/livestreamed and 21 on demand) all for less than $10 a session.

- A rich array of programming—whether it’s mastering the basics or refining research to break through brick walls—on a variety of crucial resources like New York records and repositories; methodology; migration and settlement; immigration and immigrant communities; New Yorkers of color and others whose stories have been historically underrepresented; and much more.

- Learning opportunities with the wider genealogy and family history community.

Pricing

- Virtual Member Attendance (early registration by June 14, 2024): $189

- Virtual Member Attendance (after June 14, 2024): $209

- Virtual General Attendance: $245

- In-person Member Attendance (Syracuse)*: $229

- In-person General Attendance (Syracuse)*: $265

*All in-person programming will also be livestreamed and subsequently made available on-demand through November 1, 2024. Lunch is not included at the in-person conference.

What is the New York State Family History Conference?

Researchers, genealogists, and all those interested in family history gather for the New York State Family History Conference, the largest statewide family history event held in New York. Over the years we’ve travelled to places like Tarrytown, Albany, and Buffalo, all while hosting hundreds of other researchers online. Last year's conference featured in-person and virtual programming as well as on-demand viewing of all 35 sessions.

What do I learn at the conference?

Experts on New York, genealogy, family history, and various subject material teach the sessions. Many of these sessions cover advanced topics like DNA research and searching migratory records, but others can help you build your genealogy skills and get you ready to tackle some difficult situations in your research.

Who organizes the New York State Family History Conference?

The conference is organized and run by the New York Genealogical and Biographical Society (NYG&B), a nonprofit organization based in New York City serving all parts of the State and region.

Our members are mostly from New York state but are also found around the country and world. This conference is the State’s largest event for family history and a place for all researchers to connect with others who share their interests, no matter how much experience you may have.

NYG&B members receive discounts to events like the New York State Family History Conference. Learn more about NYG&B membership.

What is the accessibility like at the Erie Canal Museum for in-person attendees?

The in-person presentations will take place in the Weighlock Gallery at the Erie Canal Museum, which is accessible by elevator.

Where should I stay in the Syracuse area if I’m coming to the conference in person?

The NYG&B does not have a hotel room block and any hotel reservations are the responsibility of registrants. We have compiled a list of local hotels in the Syracuse area for consideration.

Best Western Syracuse Downtown Hotel and Suites

416 S Clinton St, Syracuse, NY, 13202

(0.36 mi from Erie Canal Museum)

Collegian Hotel & Suites

1060 E Genesee St, Syracuse, NY, 13210

(0.73 mi from Erie Canal Museum)

Crowne Plaza Syracuse

701 E Genesee Street, Syracuse, NY, 13210

(0.43 mi from Erie Canal Museum)

Hampton Inn & Suites Syracuse North Airport Area

1305 Buckley Rd, Syracuse, NY 13212

(4.2 mi from Erie Canal Museum)

Marriott Syracuse Downtown

100 East Onondaga Street, Syracuse, NY, 13202

(0.44 mi from Erie Canal Museum)

Parkview Hotel

713 E Genesee St, Syracuse, NY 13210

(0.44 mi. from Erie Canal Museum)

Is lunch included at the conference for in-person attendees?

No, lunch is not included. In-person attendees are welcome to have lunch on their own off site or can bring a lunch to eat at the venue during the scheduled lunch break. There is no refrigeration on-site to store lunches.

What is New York Stories?

New York Stories pre-recorded, livestreamed video clips from the genealogy and family history community sharing memorable and notable stories. This special feature will be broadcast during the conference lunch breaks on September 20 and 21 and be available for on-demand viewing through November 1, 2024.

I have a New York Stories to share! How can I participate?

Many people have memorable stories; we want to hear yours! The theme of this year’s conference is "Connect at the Crossroads," and we are looking for submissions that tell stories from across New York State.

If you are willing to have your story filmed and publicly shared, please submit a brief summary (250 words maximum) of your story by July 31, 2024, to development@nygbs.org with the subject line “NY Stories Submission.” Narrated stories should be between 4 and 8 minutes long. If your submission is selected, the NYG&B will contact you to arrange a recording session.

Latest News Articles

Latest News Articles Do you have an RSS newsreader? You may prefer to use this newsletter's RSS feed at:

Do you have an RSS newsreader? You may prefer to use this newsletter's RSS feed at: